Between Muck Heap and Tractor: The Shifting Image of Farmers

The image of farmers and the countryside has been teetering between positive and negative for decades – some consider them authentic, while others find them to be conservative. What’s the reason behind this constant swinging of opinion? And how much wiggle room do farmers have today?

On October 10th, 2020, the Dutch website Nieuwe Oogst (New Harvest) reported that public opinion of farmers and horticulturists rose again for the first time since 2012. The reasons for this were new. Sustainability was already an important factor contributing to Dutch people’s appreciation of farmers, but aspects like taste, affordability, health and locality had now gained in importance. Undoubtedly, the Covid-19 pandemic had also contributed to this rising appreciation.

In Belgium, the image of the agricultural sector had also become more positive over the last two decades, after the low point caused by several hormone scandals in livestock farming and the Dioxin affair in 1999 (when toxic substances entered the food chain).

Despite a positive trend, the agricultural sector still receives extensive critique as 'green polluters' or 'animal torturers'

Despite this positive trend, the sector still receives extensive critique. Farmers are sometimes called ‘green polluters’, or animal torturers; they are accused of tampering with numbers and considered to damage water quality through over-fertilization. The image as well as the appreciation of farmers and the agricultural sector are therefore varying and diverging. And it has always been.

Horse Sense and Grumbling

Leuven-based historian Leen Van Molle describes the perception of farmers as “confusing and at the same time enlightening”. Confusing because there is no unified opinion, perhaps with the exception of farmers’ impressive capacity for physical work; enlightening because it always shows a stark contrast. Black or white, but rarely grey – this is the picture that, time and again, we paint of farmers.

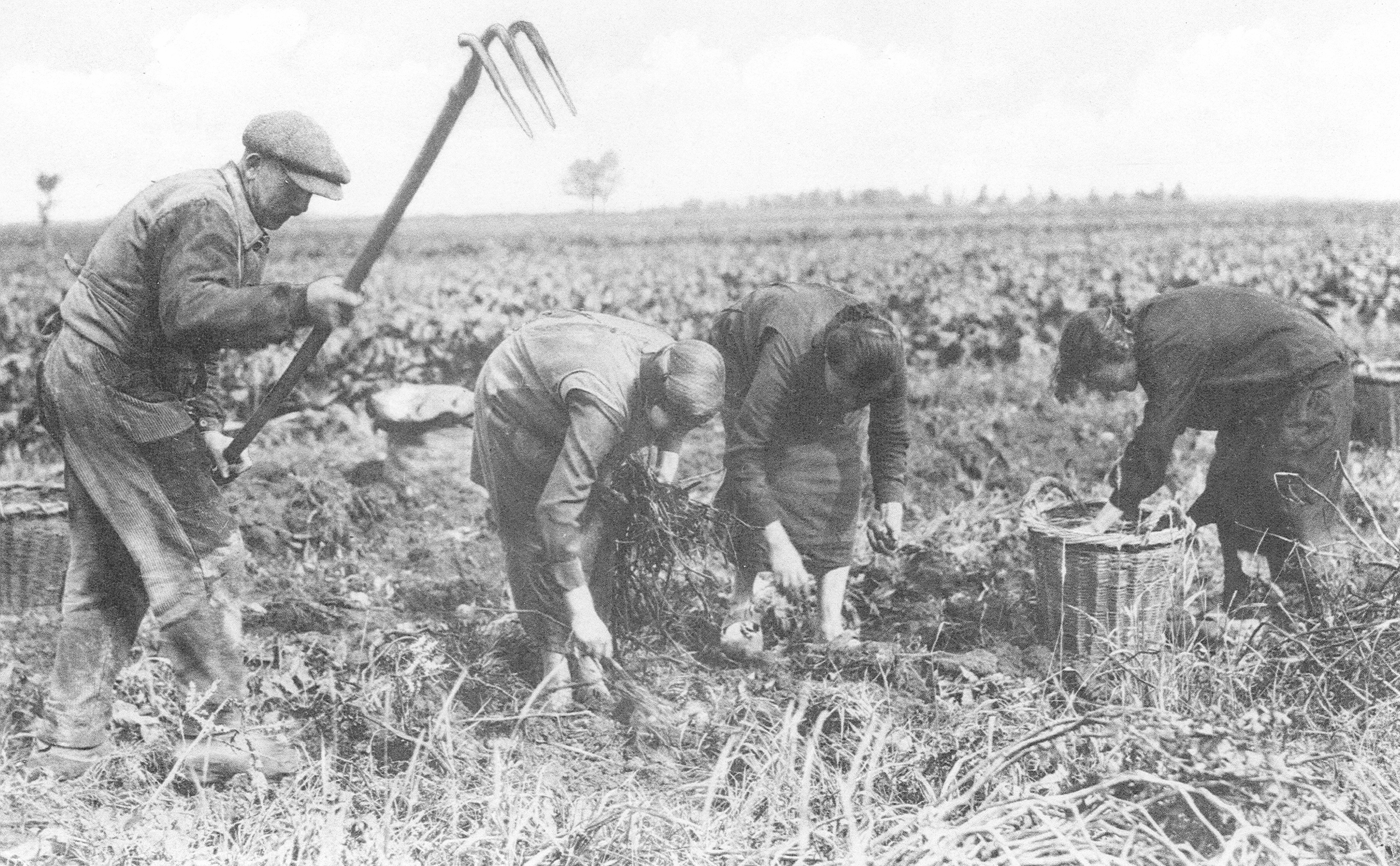

Farming in 1939

Farming in 1939How do we explain this? Among other things, Van Molle points to the dualism rooted in the farming sector itself. As the industry modernised – and it did so at an accelerated pace after World War II – the difference between innovators and those who lagged behind became more and more apparent. But there’s more at play here.

The appearance, intelligence and morals of farmers have been described in differing ways for a very long time. According to some, farmers are strong people, with enormous stamina, and strong, characteristic faces. Others describe them as materialistic, frugal, unendingly stingy and always dissatisfied. It’s no coincidence that one saying goes: “farmers and pigs are one and the same: fat and snorting”. Farmers are often put down as being stupid, backward, conservative and averse to innovation. And yet for others they are authentic: a prime example of a professional who passes on their expertise from father to son. They are sensible and unburdened by too much theoretical knowledge. ‘Horse sense’. They are also pronounced suspicious, gullible and individualistic. Yet in the same breath, rural life is characterised as a place where solidarity, neighbourly help and togetherness are far from empty concepts. Farmers were and are showered with praise, but at the same time they attract disapproval.

Two farmers, 1945

Two farmers, 1945Ⓒ Nationaal Archief / Wikimedia Commons

As early as the eighteenth century, farming and life in the countryside has captured public imagination. For some aristocrats and artists, these were metaphors for simplicity, tradition, nature and uncomplicated beauty. This positive, romantic image was especially prevalent among people who were furthest from rural society, not at all familiar with it and who were able to enjoy the luxuries of that time. Their admiration was expressed in various ways. In the parks of eighteenth century castles for example, owners strived to make the landscape look as natural as possible. Some of these landowners took this to extremes, curating their farm animals and farm workers to perfectly suit the idyllic backdrop they wished to create. And what about the French Queen Marie-Antoinette? She had a Norman farming village recreated in the castle garden of Versailles, including a water mill and livestock stables. Cattle and sheep roamed the gardens, and she even received her guests in the stables dressed as a milkmaid – uninhibited and in opposition to all etiquette.

(Part of) the urban bourgeoisie of the nineteenth century glorified the supposed simplicity and the unchanging traditions of rural life too. For them, farming life was an antidote to the political revolutions, accelerating industrialisation and the complexity of modern society in which new liberal and socialist ideas circulated. Conservative, Catholic and Protestant groups in the Low Countries, from the 1840s onwards, praised farmers as “natural” and “morally good”. They had a close relationship with nature, where according to Christian teaching, God reveals himself. Farmers served as an example to urban-dwelling people who were typified as a degenerate community, literally and figuratively further removed from God.

In their city salons or outdoors, the bourgeoisie and nobility created their own image of the countryside through literature and other artistic expressions

In their city salons or outdoors, the bourgeoisie and nobility created their own image of the countryside through literature and other artistic expressions. Painters navigated between realism and rural idyll. Realism brought a more genuine representation of farming life. Inspired by the work of Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet, among others, Vincent van Gogh painted this hard life and the bleak living conditions in works such as Peasants Planting Potatoes (1884) and The Potato Eaters (1885). Towards the end of the nineteenth century, during the socially turbulent years from 1880 to 1890, the desire for an unspoilt countryside (and untarnished nature) increased even further. For example, Emile Claus used the theme of the working peasant in his naturalistic landscapes, just like other artists who embraced en plein air and luminism.

The Potato Eaters (1885) by Vincent van Gogh.

The Potato Eaters (1885) by Vincent van Gogh.Ⓒ Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

At the turn of the century, it wasn’t only painters who travelled to the edge of the towns and to the countryside in search of untouched nature, greenery and tranquillity. Thanks to the expansion of the tram and rail network, the democratisation of bicycles and later cars, city dwellers increasingly went out on Sundays. Strolling and walking were already a popular Sunday activity, as was enjoying the healthy products the countryside had to offer. Country pubs provided refreshment and reinforcement: a hearty sandwich with soft cheese, a fresh pint or a glass of fresh milk for the ladies.

Country pub De Kroon (The Crown), near Almelo

Country pub De Kroon (The Crown), near Almelo

Novels about peasant life and by extension, regional literature set in rural landscapes, brought life on the country estate or farm into many living rooms, even though they weren’t always regarded as fully-fledges novels – certainly not by the cultural elite. However, until World War II, they were extremely popular. In Flanders, literary authors such as Stijn Streuvels (The Flaxfield, 1907) and Felix Timmermans (Pallieter, 1916) situated their stories in a rural context. Successful writers in the Netherlands included Antoon Coolen (Village on the River, 1934) and Anne de Vries (Bartje, 1935). Image and counter-image alternated in the oeuvre of these authors: the hard but honest farming life, the symbiosis between man and nature, the beautiful village life.

Loan Sharking and the Black Market

Farmers were reviled and glorified for all sorts of reasons. But there was no question that they played a vital role in food supply, and this became abundantly clear during the two world wars. With Belgium caught up in both conflicts, the image of farmers there undoubtedly reached a low point. For many citizens they became synonymous with loan sharking and swindling. A clear tension and division came to the fore: countryside versus city, or abundance versus scarcity. Farmers were accused of withholding products, selling them at extortionate prices, or adulterating foodstuffs. For example, a common complaint was that milk was diluted with water, and butter was mixed with cheaper margarine.

Farmers were reviled and glorified for all sorts of reasons, and the media played in important role in the creation of this image

Even then, the media played an important role in the creation of this image. Liberal and socialist newspapers tended to condemn the reprehensible behaviour of farmers and wholesalers, but Catholic newspapers reported in a more nuanced way. For example, they also denounced the requisition of horses and livestock by German occupying forces. The Catholic press also highlighted the fertiliser and fodder shortages that farmers had to contend with. Their message was clear: farmers were also victims of war conditions.

Alongside this, agricultural organisations were trying to present the actions of their members in perspective. According to them, not all farmers benefited from the high prices. Many farmers gave away food or sheltered city dwellers – especially children – during the difficult war years. Simultaneously, they encouraged their members not to charge exorbitant prices, and to ensure they were conducting their businesses in an ethical way. However, they did not deny that many farmers were doing good business. This also became clear in the post-war period, when the purchase of land, tools and machinery increased considerably.

Ⓒ Gozha / Unsplash

A Link in a Long Chain

From the early 1950s, the agricultural sector gained momentum. Keywords in this development were scaling up, specialisation and motorisation (from horse to tractor). This led to a respectively rapid and sustained decrease in the number of farmers and amount of farmland. For centuries, farmers were the key figures in village communities as well as the architects of the landscape. But gradually this was a position they no longer held.

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, farmers are a small minority – a separate subgroup with a specific economic activity that is no longer inherently intertwined with rural communities. The space to farm has become smaller, both in a literal and figurative sense. It was now not only the agricultural sector that could claim open spaces for their ends – industrial, residential and increasingly nature and environmental organisations raised their voices and successfully defended their interests. Gradually, the current post-productivist countryside took shape, and a consumer-friendly countryside emerged that would also take on other functions through recreation, tourism and care for biodiversity.

The modernisation of the agricultural business fuelled nostalgia further

Of course, all of this also had an effect on the image of farmers and the countryside. The modernisation of the agricultural business fuelled nostalgia further. And partly because of television (through drama series and films) the stereotypical image of farming life gained a dramatized and romanticised image. Dozens of local history groups collected objects from the rapidly disappearing ‘authentic’ village life, from ploughs and carts to blacksmith tools and the interior decoration of the village pub. In 1958–also the year of the World Exhibition in Brussels–the Bokrijk open-air museum opened in Belgian Limburg. The museum showed daily life in the countryside from the seventeenth century right through to 1950. Fermettes, better known in the Netherlands as boerderettes

(imitation farmhouses built in the traditional country style), reflected the social idealisation of the countryside, doused with a generous dose of nostalgia. These homes were generally not inhabited by farmers, but by immigrants or families who no longer had a direct link with farming. This in itself was another important post-war trend: the growing gulf between farmers and the rest of society.

Bokrijk, the open-air museum, opened in 1958.

Bokrijk, the open-air museum, opened in 1958.Ⓒ Paul Teysen / Unsplash

The diminishing familiarity with farming among an increasing portion of the population resulted in a declining understanding of the profession, subsequently contributing to their poor public image. According to surveys conducted in The Netherlands in the early 1950s, this led to a predominantly negative image of farming life. However, the extortion practices which took place during the war and memories of the economic crisis of the 1930s also played a role. As early as 1945, the Dutch Agricultural Foundation (the predecessor of the Landbouwschap) had hired an information officer whose job it was to try and spruce up the image of the sector among the general public. But in the 1950s, the focus of this role had shifted to internal information and advocacy. New initiatives followed, such as the Public Relations Agriculture and Horticulture Foundation (1964), and more recently the Friends of the Countryside Foundation, the Values of the Land project.

In a study from 1958, city dwellers described farmers as greedy, ill-tempered, stubborn and clumsy

The outcome of the first study that looked at the image of Dutch farmers among the general population in 1958, is very interesting. The respondents lived in seven large and medium sized cities ranging from Amsterdam to Enschede. The results were staggering. Negative opinions predominated, including descriptions such as ‘greedy’, ‘ill-tempered’, ‘stubborn’ and ‘clumsy’. At the same time, these city dwellers described self-employment as a positive thing, just as they regarded handling animals, working in the open air, and the tranquillity of the countryside. Their judgment wavered somewhere between ‘muck heap and tractor’, the first symbolising the less pleasant sides of farming and the second emphasising the farmer’s expertise as a modern entrepreneur.

The main conclusion, however, was that the average urban dweller in the Netherlands had very little knowledge of the agricultural sector and had a highly romanticised view of farm life. This is still reflected in the representation of the sector in children’s books, on toy packaging and in advertisements in the food industry. Television and advertisers have almost free rein to create a pleasant illusion of farming life, which hardly corresponds to the modern reality at all.

Image Enhancing Initiatives

According to the rural historian Erwin Karel, the negative image surrounding farming has changed significantly in recent decades. This is partly because the agricultural sector itself changed: small farmers have disappeared due to processes of upscaling and professionalisation. Increased mobility and the burgeoning (rural) tourism have ensured that city dwellers have discovered the countryside. Television programs such as Boer zoekt Vrouw (Love in the Countryside) have also brought a more positive (albeit somewhat romanticised) image of farming into many living rooms. However, the dual attitude still persisted in the 1980s and 1990s: positive about the farmer as an entrepreneur, but negative about the farmer as a person.

The farmer as entrepreneur has a positive image, but a negative one as a person

A more or less similar development also took place in Flanders. Since 1997, a representative group of the population has been allowed to speak out about the image of agriculture and horticulture every five years. Initially, that image was poor, mainly prompted by a number of scandals, but recently the respondents have showed more positive opinions. They appreciated the farmers’ hard work, the economic importance of the sector and the quality of their products (which are perceived as better than their imported equivalents). The majority of respondents also thought that the sector’s history of family-run business should be preserved. This positive development was a result, among other things, of the sector’s efforts to close the gap between itself and the rest of society. These efforts have included the organisation of agricultural education, farms open to the general public for visits and a national Agriculture Day.

Participants 'Boer Zoekt Vrouw'

Participants 'Boer Zoekt Vrouw'Ⓒ KRO/NCRV

However, at the same time, many Belgian and Dutch people were increasingly concerned about the impact of modern farming on animal welfare, the environment and the landscape.

The expectations of society on this matter are high and the critical voices are loud. Pointing the finger at the media, as many agricultural organisations have done, on the grounds that journalists present exaggerated criticisms compared to general public opinion, doesn’t help. This is mere rear-guard action. Farmers have to move with the times, contributing solutions to today’s challenges, as for example the consequences of climate change (think of extreme drought and lowering groundwater tables) and the problem of greenhouse gases. Driving around The Hague in a tractor or pick-up truck to draw attention to their grievances simply won’t suffice.

The agricultural sector will have to more thoroughly transform their industry into a sustainable one

The agricultural sector will have to more thoroughly transform their industry into a sustainable one. That means, among other things, that the use of artificial fertiliser and other chemical products will have to be dramatically reduced. The same challenges will have to be met in intensive farming (which caters primarily to the export market). Is there still a place for such practices in the densely populated and extremely urbanised Flanders and The Netherlands? And this is not only a figurative question, given that these activities are the cause of surplus manure production and high nitrous oxide emissions. It’s also a literal question of space: the spatial impact of this industry is large and highly visible.

The search for ever-greater efficiency and lower prices have led to far-reaching industrialisation and a growth in the scale of production. Huge warehouses and mega-barns scar the landscape in places where agricultural monoculture is on the rise. And all of this is taking place at the same time that citizens are increasingly coming to consider open spaces and countryside areas as sites for leisure and economic consumption, and as places in which biodiversity ought to be restored. The covid pandemic will likely have strengthened these views. If the agricultural sector continues to turn a deaf ear to wider society’s concerns, then public perception of the farmer and the farming industry will only suffer further.

If the agricultural sector continues to turn a deaf ear to wider society’s concerns, then public perception of the farmer and the farming industry will only suffer further

It is therefore no coincidence that the Flemish Minister of Agriculture, Hilde Crevits, pays attention to the image of the primary sector in her recent policy memorandum. Nor is it surprising that the province of East Flanders has been awarding subsidies for ‘image-enhancing initiatives in agriculture and horticulture’ since July 1st, 2020. This is of course commendable, but wouldn’t it be easier to embrace social trends and to ensure the land is farmed in a way that pays more attention to the environment, the climate, and to animals and the landscape? And of course great responsibility lies with the consumer – because at the end of the day, we all choose what we eat and which food system we want to be part of.